The term matching is a procedure where we try to find for a sample observation other observations in the sample that have similar observable features. We often refer to the selected observations as matches, and after a repetition of this procedure for all or part of these observations, the subsample of observations that come out of this is referred to as the matched sample. We have different types of matching methods. In this post, I want to talk about genetic matching. It uses an iterative algorithm to find the set of matches that optimizes the post-matching covariate balance between treatment and control groups. Genetic matching can be useful in examining the effect of a policy or an intervention.

Case study

- Problem definition and specific goals: In recent years, many countries across the world have implemented direct democracy. In emerging countries, local decisions are increasingly adopted in comminity-focused meetings. We also see a growing momentum for direct democracy in developed countries. It is the trend that motivated Sanz (PSRM, 2020) to ask: how does direct democracy affect government spending? In other words, does direct democracy increase or decrease public spending?

- Identify the data that needs to be collected: Sanz used Spain as a case study with a dataset that includes the type of political system practiced in each municpality and their respective per capita expenditure for a given year. Sanz used a quasi-experimental approach called regression-discontinuity to analyze his data. But, using his data, I will answer the same research question with genetic matching. The observed characteristics that will be used in computing the probability that a municipality will have a direct democracy are as follows: year, sh_foreign (share of non-EU immigrants); sh_eu (share of EU-immigrants); sh_young: (share of young individuals); sh_old (share of old individuals); l_g_p_votes_pp (vote-share of the right-wing PP in the municipality in the last national general elections). I chose these pre-treatment variables because they seem to simultaneously influence the treatment status (dd: whether the municipality has direct democracy or not), and the outcome variable (expenditures_c: the per capita expenditures for a given year). In addition to that, by being pre-treatment variables, this means that these covariates cannot be affected by the treatment (direct democracy) itself.

- Organize the data: I import the data into R, load the necessary packages, select the relevant variables and remove the NAs in the data.

data<- read.csv("data_spain.csv")

library(Matching);library(dplyr);library(MatchIt); library(cobalt)

data$treatment<-data$dd; data<-select(data,year,treatment,expenditures_c,

sh_foreign,sh_eu,sh_young, sh_old,l_g_p_votes_pp)

data<-na.omit(data)

- Extract features: I matched exactly on the YEAR variable, meaning municipalities can only be matched to other municipalities from the same year. Matching exactly on the YEAR variable helps to control for a lot of unobservables that are peculiar to a certain year, which could influence the outcome. More so, I increased M to 5. Although using additional nearest neighbors might increase bias, it helps to decrease variance. I then used the propensity score to estimate the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT). It ran in total for 32 generations and the solution is found at generation 21. There was no significant improvement in 10 generations in a row. In other words,even though it was meant to run up till 100, it ran only up till generation 32 because it no longer found an improvement

set.seed(666)

Xgen<-cbind(data$sh_foreign, data$sh_eu, data$sh_young,

data$sh_old, data$l_g_p_votes_pp, data$year)

gen.out<-GenMatch(Tr = Tr, X = Xgen, exact = c(F,F,F,F,F,T), estimand='ATT', M = 5,

pop.size = 400, max.generations = 100, wait.generations = 10, verbose=F)

- Analyze: The estimates of the treatment effect from genetic matching shows that there is enough evidence at 0.001 level of significance to conclude that municipalities governed by direct democracy have on average a higher public expenditure of 261.38 euros than municipalities governed by representative democracy.

m.out<-Match(Y = Y, Tr = Tr, X = Xgen, exact = c(F,F,F,F,F,T), estimand = 'ATT',

M = 5, Weight.matrix = gen.out)

summary(m.out)

Estimate: 261.38

AI SE: 30.351

T-stat: 8.6119

p.val: < 2.22e-16

Original number of observations: 14331

Original number of treated obs: 3297

Matched number of observations: 3297

Matched number of observations (unweighted): 16485

Number of obs dropped by ‘exact’ or ‘caliper’: 0

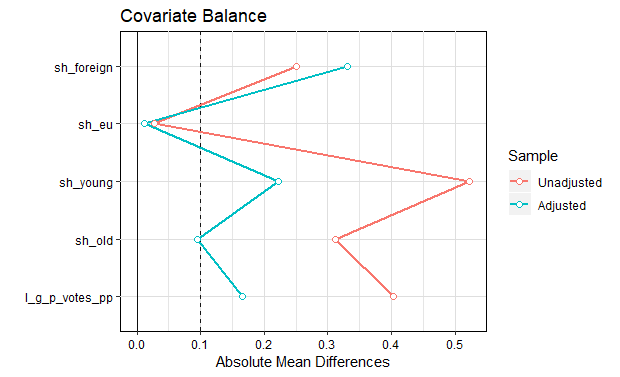

However, this estimate is only reliable if balance is really achieved after the matching procedure. That is, we should not have significant differences between the treatment and the control group.

balance.table1 <- bal.tab(m.out, treatment ~ sh_foreign +

sh_eu + sh_young + sh_old + l_g_p_votes_pp,

data=data)

love.plot(balance.table1,

threshold =.1,

line = TRUE)

The genetic matching seems to create better balance in all covariates, except sh_foreign (see figure below). But, even if the balancing condition holds on the observed covariates, imbalances in unobserved factors may still serve as cofounders, which might make the causal estimate unreliable.

- Reach an insight or recommendation: It seems that municipalities with direct democracy spend more per capita than those with representative democracy. However, these results might be unreliable due to some remaining imbalance between the treated and control groups after the matching applications.

References

Sanz, C., 2020. Direct democracy and government size: evidence from Spain. Political Science Research and Methods, 8(4), pp.630-645.