I have come across many books and articles on research methods that cover the logic of inquiry. But I have only read few that devote time to explain the logic of discovery, which Christopher Daya and Kendra L. Koivub (2018) describe “as a set of formal principles for devising a research question.” How does one come up with a “good” topic? or more accurately, a good research question?

What is a research paper?

Research simply means a search for knowledge. To be clear: a research paper is not a long, descriptive report of some event, phenomenon, or person. This is a dangerous misconception that puts emphasis on determining facts. In his book, Research Methods in International Relations, Christopher Lamont (2015) gave an example of how a student’s interest could be in the Arab Spring uprisings that started in Tunisia in January 2011 and resulted in revolutions around the world. Although the student might already have a general idea of the topic at hand due to their familiarity with media reports on the Arab Spring, this descriptive data does not necessarily direct them on how to move from collecting information on the Arab Spring to generating a research essay that makes a scholarly contribution.

So, if a research paper is not a “report” or a lengthy description, what is it? In her book, Writing a Research Paper in Political Science: A Practical Guide to Inquiry, Structure, and Methods, Lisa Baglione (2019) presented two metaphors which help explain the balance you should strive for to reach your desired end point (an excellent paper). The first is that of a court case. In writing your research paper, she argues, you are presenting your case to the judge and jury (readers of the paper). While you need to acknowledge that there are alternative explanations (e.g., your opposing counsel’s case), your task is to show that both your preferred logic and the evidence that supports it are stronger than any competing perspective’s framework and its sustaining information. Interesting details that are irrelevant to the particular argument you are constructing can distract a jury, give your opponent a chance to undermine your argument, and irritate the judge. Superior lawyers, Baglione claims, present their cases, connecting all the dots – in fact, no pieces of evidence are left hanging. The aim of all the information provided is to convince those making judgment that their interpretation is the right one.

If you consider the analogy of the courtroom too hostile, Baglione anticipates, you can also think of your paper as a painting. The level and extent of detail is determined by both the size of the canvas and the subject to be painted. A landscape with too few details can become boring and unidentifiable, whereas a portrait with too many details can make the subject become unattractive or strange. The objective, according to Baglione, is to achieve the “Goldilocks” or “just right” outcome.

Research topic

The first thing in a research process is to establish a research topic. Bear in mind that finding a good research topic involves a lot of effort because good research topics are usually very specific. The right ones won’t simply come into your head. Some students can easily identify topics of interest, such as international terrorism, human trafficking, civil conflict. The thought of working on a topic excite such students. While it may well be true that these students have no trouble selecting a general area of research, the selection is not effortless. It is also important that they narrow the topic at hand. That is, which area of the topic are they interested in? For some, the course they are taking might determine their topic. Nevertheless, they need to focus on some element that is compelling. For another group, their professor might define their topic (and even their question). A last set might be very flexible in that, for instance, they are trying to select a topic for an independent project or senior thesis. It is safe to conclude that those with multiple choices have more challenging task, but below are some strategies to help, especially when you have the freewill to decide.

Baglione (2019) identified variety of methods to come up with a good research topic. A first method is to jot down your reasons for studying political science. In addition, it could be inspiring to think about your career aspirations and extracurricular activities. A fourth way of picking a topic is to think about your favorite courses or your favorite sections of your those courses. Pick up your syllabi, books, and notes from those classes. Textbooks and readers are very good sources to generate topics. At this point, make use of the table of contents, photos, maps, illustrations, and tables to direct yourself to interesting topics. The bottom line is: you need to ponder and write down ideas from your course materials—books, articles, lectures, films, and discussions. After you’ve narrowed your interests by going through these materials, use the references and recommendations for further readings at the end of chapters to help you discover more about your potential topic and identify the major experts as well as their works that are closely related to your subject.

Another way to find inspiration for a topic that Baglione (2019) identified is to think about something that is personally important to you. Then, if necessary, take advantage of news sources that cover recent issues, such as newspapers, journals of opinion, radio, TV, or online news coverage. They tend to point out important and controversial current events. You might be able to use insights that you acquire from one of these sources as a starting point for identifying a topic. After all, highly regarded outlets tend to identify the “big stories,” which you can build on by thinking about them in more general and conceptual ways. For instance, the coverage of U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum evoke wider concepts such as “heavy industry and the rust belt,” “unions and working-class voters,” “parties and constituency building,” “NAFTA,” “free and fair trade,” or “trade wars.” In consulting news sources, use the best.

As you might have observed from the preceding paragraph, Baglione (2019) encourages the exploration of news sources that examine primarily contemporary events and controversies in thinking about topics for political science papers. She gives three reasons for this. First, students, particularly those who are undecided about on which issue to study, do not have much (historical) case knowledge. Therefore, they find it difficult to go through history and come up with something compelling and controversial. Second, she inspires students to carry out some original empirical work, i.e., a political issue or policy that no one has done before. But, this is not to say that doing an original study implies working on contemporary topics. In fact, excellent research is often done in history, political science, and sociology (and other disciplines) that examines the past again. However, her experience shows that when students choose a research paper topic about something in the past (typically one they profess to have sufficient knowledge on), they fall into what she calls the “report trap.” Finally, she wants students’ research to ask a question for which they have to know the answer (and they have not already decided on an explanation due to a past course they took, books or articles they read, and what they “just know”).

Research methodology

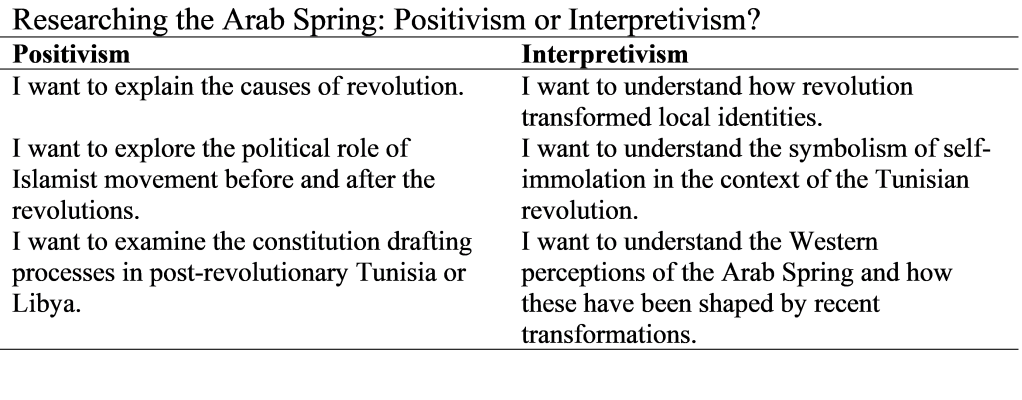

Once you have established your topic and narrowed it down, you need to decide on the methodology. Methodology refers to the way of acquiring knowledge: positivism versus interpretivism. The former is an empirically grounded explanatory research that calls for the application of natural science methods to study social reality. For the adherents of this view, it is possible to accumulate knowledge through experience and observation. The latter is a reflexive research that posits that the social world can hardly be studied through scientific methods and experimentation. The proponents of this view rejects the use of natural science methods to the social world and instead interrogates the underlying ideas, norms, beliefs and values behind politics.

You need to establish where the project lies in relation to the two epistemological perspectives. In order to decide, you should ask yourself, what your interest in a given topic is; what you want to know about it; and what kind of knowledge you want to create. Your answers will guide you in making coherent choices in relation to research design and research method. See below the example of a student interested in researching the Arab Spring:

Research question

Now that you have chosen your research topic, understood your research purpose and identified where your research is grounded along the positivism-interpretivism spectrum, you can start thinking about the framing of your research question and the kind of research design that is best suited to answer your question. Some may wonder why you need a question at all, given the existence of several interesting topics to investigate. Baglione (2019) provided three main reasons for locating a query. First, topics are too broad and contain multiple nested-issues. For instance, to become familiar with everything related to campaigns and elections in the United States or democratization around the world is a extremely demanding. So, you want a challenge that you can manage.

Second, a question directs you to a controversy; hence, there is a possibility for you to engage yourself in the scholarly and/or policy debate by both interacting with the contested ideas and exploring some information to evaluate the validity of those claims. Thus, a good question not only gives you focus but also places you in the middle of one controversy (not many). Moreover, iyou can develop your analytic skills as you weigh concepts, theoretical perspectives, and/or evidence relating to the arguments.

Third, it gives you a reason to write: you have to provide an answer. Therefore, having a question motivates you to keep writing until you have a response. By implication, it gives you a clearer indication of when you’re finished, namely when you have a systematic answer to offer.

Baglione (2019) also noted that all great research questions have seven qualities, and you can use these criteria to generate a question for study:

Interesting, important, and controversial

Research questions are interesting and important to you, scholars, the public policy community, and, in principle, ordinary citizens. By definition, then, your important query is controversial too. This means that variety of audiences are arguing over the answer in ways that are nontrivial.

Short and direct

A good question is also short and direct: if you require several lines or sentences to state your query, then you still have to refine it into one that captures people’s attention and concisely identifies a question.

Doable

Your research must be doable. In other words, you should pick a question you can actually answer with the resources at your disposal. Even when you have a first draft of that “great” RQ, you, most of the time, will discover that you need to rethink and modify the question. The more you learn about your topic and the issues involved in your question, as well as the research process itself, the more likely it is that you will choose to reshape the query. By thinking through the conceptual material, you might decide to articulate the question differently so that it becomes clearer, more focused or better addresses controversies.

Puzzling

The question should be puzzling. Many research books and articles do not devote enough attention to the issue of puzzle. To fill this gap, and to help students come up with questions and gain an understanding of research practices, Christopher Daya and Kendra L. Koivub (2018) propose a puzzle-based approach to the discovery stage of a research project. They develop a typology of empirical, theoretical, and methodical puzzles, which can direct you on how to identify research questions. They also discuss what connection exists between different puzzles and later components of research design.

By the way, Daya and Koivub provided empirical examples for each of the puzzles in their text. So, if you are interested in any of the examples, I urge you to look in there.

Empirical puzzles

An empirical puzzle is situated in real-world events. As such, these puzzles are amenable to inductive research. This creates a double task in that it requires researchers to be familiar with actual cases, and work backwards from the puzzle to discover or build an appropriate theoretical framework. While empirical puzzles require one to be familiar with theory or conventional wisdom, they are primarily based on a researcher’s case knowledge. Undergraduates are likely to find empirical puzzles the most accessible mode of discovery because they are situated in real-world politics.

Daya and Koivub identify three types of empirical puzzles. First, a “contra expectations” puzzle is when a phenomenon occurs that go against the conventional wisdom or theoretical expectations about a widely held understanding.

Second, a “divergence/convergence” puzzle is a set of cases that do not relate to

each other in an expected way. This type is equivalent to the Millean methods of

agreement and difference. Divergence is when multiple cases that look the same have different outcomes. Convergence is when multiple varying cases experience similar outcome.

Finally, a third type of empirical puzzle is “variation over time.” This occurs when seemingly stable conditions of a political phenomenon suddenly change. What explains this sudden or dramatic change?

Regarding research design, Daya and Koivub advised students to move from the research question to case selection, concept formation, and then the literature review when dealing with empirical puzzles. While selecting a case is an inherent part of the process of identifying empirical puzzles, finding the body of literature into which the project properly fits might pose a challenge. Students should select cases based on the research question, and then conceptualize and operationalize the outcome of interest. They can then use this to guide their review of literature.

Theoretical puzzles

Theoretical puzzles are found in gaps or contradictions in existing literatures. Largely deductive, such puzzles require familiarity with a particular body of theory, and pose challenges of case selection in order to test a new theory. Learning how to identify a theoretical puzzle can be difficult for many undergraduates, and may be more suitable for graduate students. Daya and Koivub (2018) identified three types of theoretical puzzles.

The first is “conceptual omission,” in which a body of literature only addresses one type of phenomenon, when theoretically other types of phenomena could exist. Second, a “theoretical convergence” puzzle is when one body of literature is used to examine another, unrelated body of literature. Third, “squaring the circle” puzzles put contradictory theoretical arguments against one another and look to identify an alternative approach to understanding particular phenomena.

Theoretical puzzles require an in-depth knowledge of theory, but can easily be used to generate testable hypotheses and, more practically, write a literature review. With this type of approach, however, Daya and Koivub (2018) argue that finding cases that are appropriate for testing those hypotheses can be hard. Furthermore, if one finds an appropriate case, it may not be feasible to study, perhaps due to language barrier or access. Here. they recommend students to begin with a literature review, then turn to hypothesis generation, and then look for appropriate cases.

Methodical puzzles

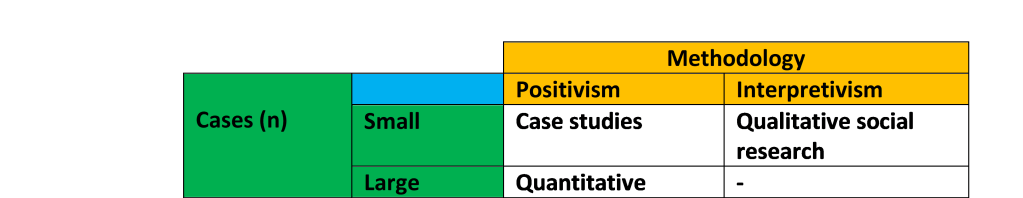

If I have understood the method classes I took correctly, it is safe to say that when there are large numbers of cases (large-N) involved, quantitative research methods are usually applied. When there are a small number of cases (small-N) involved, either (positivist) case study method or (interpretive) qualitative social research is usually applied. But Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is an alternative method that could be applied to either intermediate-N or large-N studies. QCA techniques are intended as methods for “bridging the gap” between qualitative (case study oriented) and quantitative (variable oriented) approaches in social science research. But its application is based on the assumption that there are interaction effect between variables.

Methodical puzzles identify an ongoing debate to which a particular method has not yet been applied. As such, these puzzles require one to already have very good knowledge of methods. Here, Daya and Koivub (2018) distinguish two types of methodical puzzles. First, a measurement puzzle is when one finds a new way to measure a particularly difficult concept. Second, a technique puzzle is when one attempts to resolve an enduring debate by applying a new method.

For Daya and Koivub (2018), methodical puzzles naturally lead with methods for hypothesis generation and testing, and can take advantage of a researcher’s unique skill set. Measurement puzzles in particular direct the researcher’s attention toward concept formation/operationalization. However, they advised students to start with the relevant literature before concept formation and case selection. Also, they argue that a review of the literature lets the researcher identify the shortcomings of existing explanations, and may result in a more refined concept, as well as ideas for selecting cases that re-test past empirical applications.

Additionally, methodical puzzles are useful with new methods that have advantages that conventional methods lack. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), for instance, can be used to study “conjunctural causation”, which is believed by some to be an improvement over regressionbased approaches to interaction effects. With QCA techniques, researchers can identify poorly understood conjunctural phenomena, and use existing literature to retest hypotheses.

Conclusion

Start from your topic and purpose and ask yourself: do you want to explain events in the world “out there”? or do you want to question the social meaning of a particular practice in international politics? Once you have established your research topic and purpose , you can then go on to thinking about your research question while making sure that your research has the good qualities identified by Baglione (2019). Finally , the empirical, theoretical, and methodical puzzles by Christopher Daya and Kendra L. Koivub (2018) are useful tools for any student in formulating a research question. Above all, using a puzzlebased approach to formulate a research question is extremely helpful for the subsequent stages of research design.

On the one hand, empirical puzzles take advantage of a researcher’s case knowledge and are likely easier for undergraduates to carry out. These puzzles clarify from the begining the suitable cases but demands scholarly attention at the concept formation stage to situate the question in the appropriate literature. Theoretical puzzles, on the other hand, lend themselves well to situating the research question within the extant literature. But, it can be hard to select cases, especially due to language barrier or inaccessible region for field work. While both empirical and theoretical puzzles are useful for identifying an appropriate methods, methodical puzzles can lead to the use of new methodical techniques to answer enduring or unresolved contoversies.

References

Baglione, L. A. (2019). Writing a research paper in political science: A practical guide to inquiry, structure, and methods. Sage.

Day, C., & Koivu, K. L. (2018). Finding the Question: A Puzzle-Based Approach to the Logic of Discovery. Journal of Political Science Education, 1–10.

Lamont, C. (2015). Research methods in international relations. Sage.